“Mr. Jones,” a feature film written by Andrea Chalupa and directed by the Oscar-nominated director and screenwriter Agnieszka Holland, is a joint Polish, Ukrainian and British production that was premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2019 and released in the United States in April of this year. Its Ukrainian title is “The Price of Truth,” and at its center is one man’s struggle to get to the truth about Joseph Stalin’s famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933, which the regime was hiding from the outside world on the eve of the diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union by the United States.

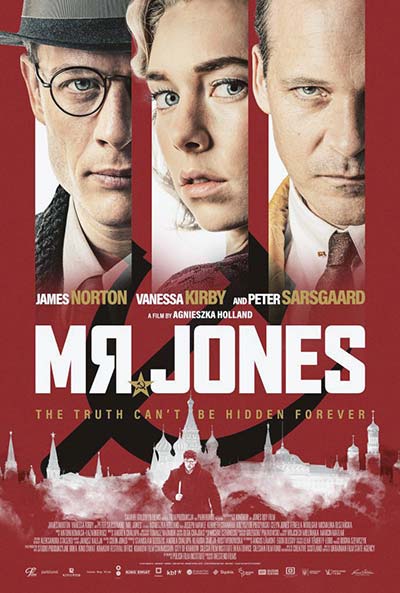

Poster for the film “Mr. Jones” by Agnieszka Holland, with screenplay by Andrea Chalupa.

“Mr. Jones” is based on real people and real events. The movie’s central character is Gareth Jones, a young Welsh journalist who travels to the Soviet Union in the early 1930s hoping to interview Stalin. Instead, he ends up uncovering the dictator’s big secret, the Ukrainian famine. Jones’s principal antagonist is the Pulitzer Prize-winning Moscow correspondent of The New York Times Walter Duranty, who uses his considerable status to publicly attack Jones and deny the existence of the famine. The two leading actors, James Norton (Jones) and Peter Sarsgaard (Duranty), brilliantly capture this struggle for truth during what was one of the darkest periods in European history.

The film speaks to today’s problems and concerns in a very powerful way. In this era of the fake news and alternative facts, “Mr. Jones” sends out a consequential message about the importance of truth and the responsibility of the media to tell it, despite the never-vanishing desire of authoritarian regimes and unscrupulous politicians to hide the truth about their actions.

But “Mr. Jones” is not only about politics, it is also about history. Many viewers will be stunned by the events depicted in “Mr. Jones” and will come away encouraged to explore the subject in further detail. They will soon discover that debate continues to rage over exactly what Gareth Jones witnessed in Ukraine in March 1933.

The film’s suave villain, Walter Duranty, was only the first in a long line of Western journalists, academics and intellectuals to deny the reality of the famine. This denial has taken on different forms over the past nine decades. It began with outright refusals to recognize the famine, before later evolving into attempts to reject the deliberate character of the mass starvation that resulted in millions of Ukrainian deaths.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the discussion has centered around whether the Holodomor qualifies as an act of genocide. This was the definition given to the famine by no less an authority than Raphael Lemkin, the lawyer who coined the term “genocide.” Despite this seemingly decisive verdict, others continue to insist the Holodomor was not genocidal. Tellingly, these arguments remain primarily political rather than academic in nature.

What exactly did Jones encounter in Ukraine? In March 1933, Jones took a train from Moscow to Kharkiv, which was then the capital of Soviet Ukraine. As the train drew close to the Russia-Ukraine border, he disembarked surreptitiously and continued his journey on foot. While there was evidence of food scarcity on the Russian side of the border, it soon became clear that Ukraine was in the midst of a vast and deadly famine.

“In almost every village, the bread supply had run out two months earlier, the potatoes were almost exhausted, and there was not enough coarse beet, which was formerly used as cattle fodder, but has now become a staple food of the population, to last until the next harvest,” Jones wrote a few weeks later in a letter to the editor of the Manchester Guardian newspaper [the forerunner of today’s Guardian newspaper].

“In each village I received the same information – namely that many were dying of the famine and that about four-fifths of the cattle and the horses had perished. One phrase was repeated until it had a sad monotony in my mind, and that was: “Vse opukhli” (“all are swollen from hunger”), and one word was drummed into my memory by every talk. That word was “golod,” meaning “hunger” or “famine.” Nor shall I forget the swollen stomachs of the children in the cottages in which I slept.”

Upon leaving the Soviet Union in late March 1933, Jones issued a press release about his recent experiences in what he called the “black earth region” of the Soviet Union. It was picked up by several newspapers, but not The New York Times. Others proved equally unwilling to accept reports of the famine. Those who, for ideological or other reasons, were sympathetic towards the Soviet Union, did not want to hear about people dying of hunger in the fledgling socialist paradise. The chorus of denials included some of the intellectual heavyweights of the age such as George Bernard Shaw, who signed a collective letter to the Manchester Guardian which accused the British media of presenting “the condition of Russian workers as one of slavery and starvation.”

The main rebuttal to Jones came from Duranty himself via an article published in the March 31, 1933, edition of The New York Times. This masterpiece of disinformation directly attacked Jones, accusing him of jumping to the conclusions on the basis of limited facts and not telling the entire story. “Conditions are bad but there is no famine,” wrote Duranty.

While dismissing talk of mass starvation, Duranty echoed Soviet propaganda by acknowledging “food shortages” due to mismanagement and sabotage within the agricultural collectivization process. Notoriously, The New York Times correspondent also shared his own thoughts on the situation in Ukraine. “To put it brutally, you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs,” he wrote. This chilling line appears in “Mr. Jones.” It is perhaps the ultimate testament to the cynicism that allowed Duranty and his fellow Moscow correspondents to cover up the mass murder of millions.

There is no suggestion that Duranty’s denials were ideologically driven. The Liverpool-born journalist was anything but a Communist fellow traveler. His chief motivation in concealing the Holodomor appears to have been a desire to maintain his high standing in Soviet Moscow and his access to leading Bolsheviks. Having won considerable fame for his coverage of the Soviet experiment and his earlier interview with Stalin, Duranty seems to have had few qualms about following the party line as Ukraine starved.

Beyond the many obvious ethical issues they raised, the criticisms leveled at Jones were also factually dubious. Duranty accused the Welshman of presenting “a rather inadequate cross section of a big country.” In reality, by journeying through the Russian-Ukrainian borderlands and testifying to the different conditions he encountered in Russia and Ukraine, Jones had unknowingly stumbled upon a major characteristic of the Holodomor. Far from being a natural disaster, this was a famine that followed national and political boundaries.

The immediate cause of the famine was Stalin’s drive to gain control over the Soviet Union’s agricultural sector in order to finance his ambitious industrialization and militarization plans. This meant forcing millions of peasants onto collective farms. As resistance to collectivization grew in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Ukraine became a focal point of peasant uprisings. In response, Stalin deployed the secret police to conduct larger-scale deportations while continuing with collectivization and the requisition of grain.

By spring 1932, the removal of grain supplies had led to famine in parts of Ukraine. Within a year, virtually the whole of Ukraine was suffering from mass starvation. Other grain-producing areas of the USSR were also experiencing famine, including Kazakhstan and the Kuban region of the North Caucasus, which was largely settled by Ukrainians.

The available evidence indicates that Stalin used the crisis to crush what he considered to be Ukrainian nationalism, manifested in Ukrainian resistance to collectivization. As a former people’s commissar for nationalities, Stalin was well-versed in the intricacies of national identity within the USSR. He believed the cultural accommodation of Ukrainians during the early years of the Soviet Union had strengthened rather than weakened their resistance to the regime. It was an error he sought to correct.

In December 1932, a few months before Jones’s trip to Ukraine and as famine conditions continued to worsen, Stalin launched a major attack on the Ukrainian language and culture. In the regions of Kuban settled by Ukrainians, these measures resulted in the closure of all Ukrainian schools, cultural institutions and newspapers. Stalin was not only going after Ukrainian grain; he was also targeting Ukrainian culture and, ultimately, Ukrainian identity itself.

In contrast to the parallel collectivization process in Russia, the famine in Ukraine was not restricted to grain-producing regions. The impact of the Holodomor extended to parts of the country that were never considered part of the fabled Ukrainian breadbasket. This included the Kharkiv borderlands of Ukraine that Gareth Jones visited in spring 1933.

Jones’s journey took place before the worst months of the Holodomor. The death toll in Ukraine would not reach its peak until June 1933. Overall, close to 1 million people are believed to have died in the Kharkiv region alone. More than half of the estimated 4 million Ukrainians who lost their lives in the famine perished in regions that did not belong to the country’s grain-producing agricultural heartlands. The only reason these areas suffered so badly was because they were part of Ukraine.

As famine conditions began to recede in late summer 1933, the denials took on a new tone. In an August 1933 article for The New York Times, Duranty belatedly recognized that the “food shortages” cited in his earlier reports had in fact been a large-scale famine. He acknowledged that up to 2 million people had died, but he refused to attribute this to the actions of the Soviet government. Instead, his focus remained on discrediting opponents while trumpeting the bright future of the USSR. The first sentence of his article read: “The excellent harvest about to be gathered shows that any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda.”

This continued whitewashing of Stalin’s Ukraine famine proved internationally convenient. At a time when the democratic world was far more concerned by Hitler’s recent rise to power in Germany and the economic impact of the Great Depression, there was little appetite for a confrontation with the Kremlin.

Indeed, as Ukraine starved, the United States was preparing to extend official recognition to the Soviet Union. Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage of the USSR was widely seen as important in influencing U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and convincing American public opinion of the need to open diplomatic relations with the communist state.

At the dinner given for Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in November 1933 to celebrate the establishment of relations between the United States and the USSR, Duranty’s presence was greeted with the most thunderous applause of the entire evening. This triumphant scene for Stalin’s greatest apologist appears in Agnieszka Holland’s movie. It has little in common with the happy endings typical of Hollywood blockbusters, but it is a fitting finale to a true story that has much to tell modern audiences about the dangers of disinformation.

Serhii Plokhii is the Mykhailo Hrushevsky Professor of Ukrainian History and the director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University.

The original version of this article appeared on the Atlantic Council website under the title “ ‘Mr. Jones’ brings Stalin’s Ukraine genocide to international audiences.”